‘Do You Like Me, Mommy?’

An Immigrant Mother’s Battle with Rejections

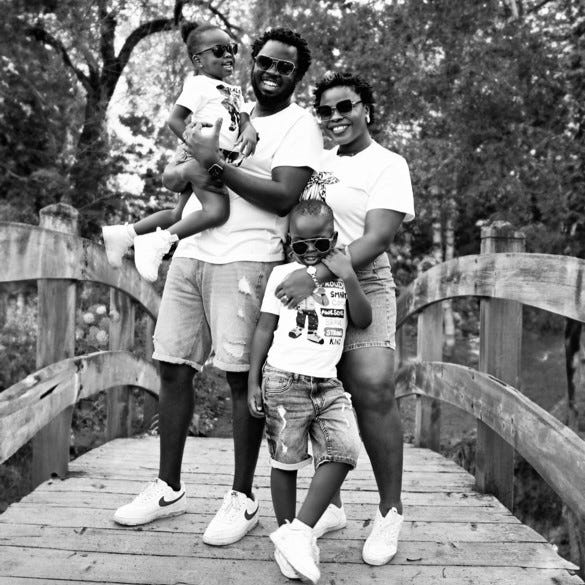

Family played a major role in Sophia’s decision to move from Nigeria to Canada. Two years before applying for her master’s program and student visa, she had considered travelling to Canada for health tourism to have her second child. However, her baby arrived earlier than expected, and since Sophia had long aspired to pursue a master’s degree abroad, she and her husband decided to make the move. Other push factors, such as rising concerns about police brutality in Lagos, also influenced their decision.

When Sophia and her husband decided to leave Nigeria, they considered other countries, but Canada stood out. “It felt more family-oriented than the others, and that meant a lot to me," she explained. "Families here really prioritise spending time together, like having dinner and enjoying the small moments. That attention to family life kept us drawn to Canada. I wanted to give my children the chance to experience a happy, close-knit family environment.”

In late 2020, Nigeria saw a wave of protests against police brutality, culminating in an incident where army officers killed and injured civilians—a tragedy now known by some as the Lekki Massacre, which occurred at the heart of the nationwide demonstrations. By the end of the following year, Sophia and her husband were on their way to Canada.

“I Had My Plans”

In Nigeria, Sophia and her husband ran a production company that created commercials and music videos for well-known brands. Before that, she worked in various roles in television, giving her solid media expertise as she relocated to Canada.

She explained, “I had my plans. I was going to jump right in, join the workforce, and start living the Canadian dream. But as a mother, no one prepares you for the reality of not finding a day care spot for your child. As soon as we moved, we started searching for day care, but that marked the beginning of my worst nightmare as an immigrant mother. The first day care I enrolled my son in sent him back after a week. Their reason? He was ‘too energetic and too active.’”

Sophia’s son was three years old when they moved to Canada. He had reached his milestones early and impressively. For instance, he barely crawled—just a few days before his first birthday, at a party, he stood up and started walking. He also learned his ABCs early and mastered them quickly. When he started school, he was a bright, active child with no complaints about his behaviour or social interactions.

‘Do you like me, Mommy?’

When her son started at the first day care, Sophia had just secured her first job, which allowed her to work from home. It was an ideal setup since she still had her toddler daughter and was also juggling her studies. But when her son was rejected, Sophia had no choice but to quit her job—it was impossible to manage two kids at home while working. This forced her to begin the day care search again. It was a challenge they faced three times, and the impact on their lives was significant.

The effects were multifaceted. According to Sophia, her son started crying when he was told he couldn’t return to the day care. At the next day care, he was rejected after one month, with the staff claiming he had flipped a desk, among other issues. “I had no way of knowing what really happened in that day care, but it was clear they were mistreating him,” Sophia recalled. “The words they used to describe my son, the narratives they created, were just... heartbreaking.” A sombre Sophia explained that her son, who was sensitive and perceptive, began to regress after being sent away from the second day care. “He stopped talking as much and became afraid of white children when he saw them at the park—he would avoid them. I don’t know what happened there, but he showed all the signs of trauma. He wasn’t the same boy we brought here. He would wake up screaming at night and barely slept.” With her son back at home and acting differently, Sophia had to resign from her second job and once again started searching for day care.

She also noticed that her son had become increasingly concerned with people’s approval, constantly seeking reassurance in ways he hadn’t before. “He would always ask, ‘Do you like me, Mommy? Does Aunty like me?’” she said. When her daughter finally secured a day care spot, it had a profound effect on him. Every morning, as his sister left for school, he would cry, and Sophia would often cry with him.

‘Shame’

To adjust her expectations, Sophia began searching for short-term jobs. After her son was admitted into another day care, she managed to secure a position at the mall. “On his first day, I was still signing in at the mall when I got a call—they told us to come pick him up. They wouldn’t take him anymore. It had only been three hours since we dropped him off that morning. That was the moment that broke me completely,” Sophia shared. “I gave up. I stopped applying for jobs. I became a sad, angry, regretful woman, and turned my focus to just taking care of my kids. I saw parts of myself I never want to see again. I felt guilty for wanting to work when my child was going through something I couldn’t understand. I’d tell myself I was a useless mother. At the same time, I did as much as I could to teach him how to act when we stepped outside, and I started homeschooling. I changed our diet, and just threw everything that I had at it”.

It wasn’t just the fact that Sophia could no longer work; it was the fear that her son might not be accepted into any school. More crucially, the repeated rejections were visibly affecting her son and their family dynamic. “I gave up on my parenting skills,” Sophia admitted. “I felt like I didn’t know my own child. I began to see him as the problem, like this wasn’t my son anymore, like something was wrong with him. Emotionally, our family started to unravel. We stopped going out with him—we were hiding, shrinking. If I took him to the store, I was always terrified he’d do something wrong. The rejection and the words from the day care centres just filled me with fear.”

Desperate to figure out how to help her son get better prepared for school, Sophia saw a paediatrician. After an initial assessment, she was told that there was a possibility he might be on the lower end of the autism spectrum. Behavioural therapy was recommended. “I’d had this child for three years and we’d never been to the hospital except for routine check-ups. He was born healthy and perfect. I came here to give him a better life, not to complicate things for him,” she said.

Coming from a culture that doesn’t handle difference or special needs well, she admitted she dealt with shame. Fearful of her family’s reaction, she kept the paediatrician's comments and much of her struggle to herself, which only worsened her mental health. At the same time, she was aware that giving up would mean letting her children down, so she did the best she could to manage her emotions.

‘Mummy, I like it’

During this time, Sophia was actively trying to find new spaces for her son to socialise. Being a person of faith, she decided to visit local churches. Within a 12-month period, she attended at least 12 churches before finding the one she now calls home. When asked if her difficulty in settling into other churches had anything to do with race or cultural differences, she explained, “I wasn’t looking for a black church. I was looking for a community for my son—somewhere no one would tell me there was something wrong with him, where I wouldn’t feel anxious, and where I wouldn’t be constantly checking the door, worried a teacher would come and ask me to take him away.”

Curious about what made this church different, I asked Sophia why she chose to stay. “At the end of the service, my son said to me, ‘Mummy, I like it,’” she recalled. Through tears, she added, “from that day, every morning when he woke up, he stopped crying about not going to school and started asking when he could see his friends. He finally felt at home.”

‘Until You Build or Join a Community, It’s a Lonely Life’

Throughout our conversation, I wondered why Sophia hadn’t mentioned any support from the Nigerian community in her province. As a Nigerian immigrant myself, I know that Nigerian—or at least African—religious and cultural groups can be found even in the most remote places. These communities are often formed around the shared experience of navigating life as immigrants. Surprisingly, Sophia didn’t know the Nigerian community existed.

During her first year in New Brunswick, Sophia’s only real communication was with her two children, her husband, and friends back home. She hadn’t known about the Nigerian community until she joined her faith group. The day after her first visit, one of the Nigerian women came to see her. “I remember just leaning into her and crying,” Sophia recalled. The relief was immediate, but so was the regret for not finding them sooner. Once she connected with the community, she quickly learned that her struggles with her son weren’t unique. Other mothers shared similar experiences. “If I had known there were people to talk to—people who understood—I wouldn’t have felt so alone,” Sophia said. “They told me how I could have advocated for my son, and I realised I didn’t even know I could do that. Sometimes I still relapse and fall back into the mindset that first year put me in. I wish I never had to go through it, especially alone.”

Finding people to connect with—whether to hang out, shop together, or simply share experiences—brought enough light into Sophia’s life that she finally found the courage to pick herself back up.

On a random day, during a family outing, her son picked up a piece of paper, read the words in English, then flipped it over and read the French text aloud. At that point, Sophia hadn’t taught him to read yet, and she doesn’t speak French. It brought her to tears. “This was the moment it hit me that nothing was wrong with my son,” she said. “I started gaining my confidence back. I told myself that this was just a process and what he needed was a chance to settle in.”

“There’s Just a Gap in Understanding”

As harrowing as the experience was, Sophia doesn’t place the blame on any one party. “I really don’t blame anybody. Nobody asked me to pull my son out of school in Nigeria and bring him 6,000 miles away. It’s my responsibility to advocate for my children, to tell people what they need to know about them, instead of just accepting everything they say to me,” she said.

Sophia also expressed how parents often underestimate the impact of immigration on children. She likened the process to replanting an orange tree in a new spot: “It will go through a season of withering, and it may seem like it’s dying, but it will come back. You have to create the right environment for that. Just like adults, children deserve the chance to grow into this new life.”

Since her experience isn’t unique, she believes that the day care centres could benefit from greater awareness about how to support recently immigrated children.

Looking back, Sophia wishes she had started preparing her son for the transition earlier, while they were still in Nigeria. “I would have made changes around food and routine, like some parents do,” she explained.

Now, Sophia dedicates some of her time to helping others who are planning to move abroad, offering advice on how to ease the transition.

Finding the Right Fit

Forty-eight hours before starting her new job, Sophia was still desperately searching for a sitter for her son. With her awakened sense of optimism, she had re-entered the job market and secured a role she loved at a media organisation. But with only hours left until her first day, she faced the possibility of losing yet another opportunity. She even drafted an email to her new employers, requesting to postpone her start date by a month. Just before sending the email, a Canadian woman who had seen her post on Facebook reached out and offered to babysit her son.

“It was the riskiest thing I’ve ever done in this country,” Sophia said. “We went to her house on Saturday, met her, agreed on a price, and by Monday, we dropped my son off. She is the reason I’ve been able to keep and enjoy my job. She takes him on out to socialise and learn, and combining that with the behavioural therapy he’s getting has made such a difference. I’ve watched my son grow more confident. He’s becoming the child I knew in Nigeria, just an older, better version. He started kindergarten and he is doing well.”

As Sophia reflects on her journey as a mother, she says she’s learning to accept the different versions of herself that have emerged through these challenges. She’s proud of her resilience and her ability to rise, like a phoenix, from adversity. “I went from a struggling, ashamed mother to just another immigrant next door who’s thriving,” she said. “Through this experience, I’ve seen two sides of myself—the dark and the light—and I’m grateful the light always breaks through.”

Beautifully written🥹❤️